Why she had to flee from North Korea

As part of its important activities, LFNKR has been supporting former North Korean defectors who come to Japan and resettle. Ms. Kim SH is one of the defectors whom LFNKR has helped to build up her new career in Japan. In her busy daily life, employed as a medical worker, she frequently provides LFNKR with utmost help in its activities, such as events related to North Korean human rights issue, often as a speaker describing what life is like in North Korea.

On July 29, she was invited by a citizen’s group in Tokyo to talk about her life in North Korea and the ordeals she has experienced after she fled from her country.

—

I was born in a local city of North Hamgyong. My parents were Koreans born in Japan and moved to North Korea later. They were medical workers, but my mother stayed at home after marriage. My family was relatively wealthy in North Korea. But, when I was a senior at a university in Pyongyang, I decided to escape from North Korea. I am sure that many people wonder why I decided to defect while I was born into such wealth. If it had been possible, I would rather have stayed at home with my family, of course.

Then, why did I have to leave my country? Today, I want to talk about some aspects of the lives of people in North Korea. This may explain my reasons.

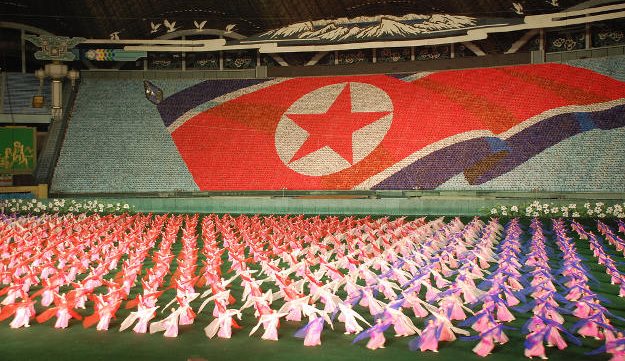

I know that many people have typically heard about North Korea’s nuclear weapons, their deaths from starvation, and their mass games. Also, I’m sure the hyper-dramatic speaking style of North Korean newscasters is well known.

The moment we are born in North Korea, we face a society of extreme surveillance. We monitor each other and zealously blow the whistle the moment we see anything suspicious. If we should fail to do that, then we fail to protect ourselves and our families. If we don’t do that, we could be sent to prison. This is the society in which I was born and raised. So, every one of us is conditioned to be an informer.

As a matter fact, one of my close neighborhood friends once commented in a casual conversation that our government was wrong, and the next day, her whole family were arrested. They simply disappeared. This was not the only case I witnessed. There were others.

From earliest childhood, my parents consistently warned me never to say anything related to Japan, not even to my closest friends.

Needless to say, we have no freedom of speech … no freedom of anything. We have no freedom to choose our clothes, our hairdos, nor even the lengths of our skirts, etc. Young students like to wear short skirts, but if we go out wearing skirts that are even slightly short, then we are very likely to be caught at check stations. We have quite a few check stations. Once caught, one has to write every detail about oneself, including name, address and school. Sometimes, we are required to let them check everything in our bags. If they find anything that they consider undesirable, we are in big trouble. Even if it’s just a minor non-compliance in our clothing, it will be reported to our schools. We must compose essays repenting our misdeeds and read them aloud in front of the entire student body and face their criticisms.

We have to state “I sincerely regret having worn a dress of capitalism.” In a bad case, we might be subject to forced labor. In the worst case, we are sent to a labor camp. Even though we are students, they show no mercy.

Also, the national security officials come to our houses regularly to thoroughly check all belongings in our entire house, including all the drawers. I know that many people who had come from Japan were sent to labor camps because the national security officials found Japanese magazines or tape recorders that those people had secretly hidden. Many people were taken away just for saying, “We don’t know why we came to North Korea. Please let us go back to Japan.” To this day, their whereabouts remain unknown.

Since I was a little girl, I was used to seeing people handing bribes to the officials who visit them. Initiating a bribe at the earliest stage is a must to prevent arrest. Typical bribes are cigarettes. We have to immediately hand them gift cigarettes as soon as they find anything that might be a problem.

You have probably heard the word “Kippumjo” (pleasure squad) of North Korea. It’s a group of young, beautiful women strictly screened from all over the country to serve and provide pleasure to the Kim family, as well as to army officers and party officials. The screening of candidates begins with girls in elementary school. Some women feel proud of being selected to join the pleasure squad.

For men, there is the screening for becoming security staff responsible for guarding VIPs in North Korea. The screening items include face, height, health condition and family background. This screening for candidates also starts with boys in elementary school. Some boys change when they reach high school age, but if the examiners don’t find any problems with the candidates that were selected in elementary school, then the selected young men are taken for training.

Behind this, there is a sad story. The parents of the selected boys are required to offer their sons to the country, and the parents must get rid of all personal items, including photos, of the sons and pretend they never existed. The neighbors, of course, know what happened to those sons but must never mention anything to anyone. There are quite a few cases where parents secretly hide one photo of the son who was taken and repeatedly take out the picture and weep.

Refusal by families or their sons to serve the government would be considered treason, and the entire family would be taken away. Once gone, they are never heard from again. There are countless cases just like this.

You may wonder how in the world has the government in that country remained in power? Why do the people remain silent? They should dramatically protest the government’s actions and policies. But, as I mentioned, the nation is based on a highly developed informant society. When three or four persons get together, we just don’t know which one could be an informant. So, we make no plans, take no actions to protest against the authorities. In the past, some people have tried, but ended up with all their family members in prison. Not only close family members but all their relatives are also jailed. If one family member does something against the authorities, then all members of that family for three generations are arrested. So, an extremely remote relative that we have never met and never even knew was related could endanger an entire family.

Also, the authorities thoroughly control the media to prevent people from getting access to information from abroad. People remain ignorant and are made to believe that what they have is the same everywhere in the world. This ignorance and the fear of causing all family members and relatives to be killed lead to their hesitation to take any action.

Recently, in Japan, several persons who once belonged to a Japanese cult called “Aum Supreme Truth” were executed for murder. When news of the execution was broadcast, quite a few voices were raised questioning whether the execution was really justified. This debate would be absolutely impossible in North Korea.

In North Korea, if a wife is sentenced to death, it’s customary to make her husband sit in the front row closest to his wife when she is executed. In fact, there is a widely known case where this happened. In the 1990’s, there was a very beautiful actress in North Korea. She was married but had affairs with a number of executives and wealthy men. One day, in a garage, she was having sex with the son of a wealthy family that regularly donated large amounts of money to the regime, and he died from carbon monoxide poisoning. She was accused of lewdness and sentenced to death. At the execution, her husband was forced to sit right there in front. This is a well-known story. I was born and raised in such a country.

First ship carrying ethnic Koreans from Japan to “Paradise on earth” in North Korea sailed in 1959

My parents are from western Japan. That is, they are ethnic Korean residents born in Japan. In the 1960’s, when they were junior high school students, their entire family moved to North Korea, having been encouraged by the infamous “Paradise on Earth” campaign.

I am convinced that every one of those who moved to North Korea experienced a living hell. I was born and raised in North Korea, so I naturally accepted everything I was told. But my parents had lived in Japan and so they knew a great deal about Japan. My parents told me that they were discriminated against in Japan but that it was nothing compared with the discrimination in North Korea. Those people who emigrated from Japan were treated much more harshly than the local people were.

My parents were not free to speak openly, and I am sure they had a hard time in that environment. At home, however, my mother and father told me much about Japan and their friends with whom they enjoyed visiting many sites in Japan. My parents seemed to really wish they could escape from North Korea someday, because they believed that something was seriously wrong with the country. They often said this, but they knew that if they should be arrested trying to escape, they could face prison camp or execution. This is why they hesitated to take a first step to escape.

In addition, there are many checkpoints between my parent’s house and the China border, and we would be asked why we wanted to cross the border. Also, we would need travel permits. We could use bribes to get permits, but if we were caught for any reason, then the whole family would be in grave danger. So, all the more, we were reluctant to take the first step.

I managed to enter a university, but during my junior and senior years, I started feeling deep distress, because I could see no hope for the future. Everything was up to the government; they would always decide my future and there was no way for me to participate in decisions regarding my own fate. The authorities tell us where to go and what to do. People from Pyongyang might have some chance of making their own decisions if they have connections, but I am not from Pyongyang and have no connections. My family was wealthy in our little rural area but could not compete with the level of wealth in Pyongyang.

In the meantime, I heard a rumor that I might be sent to a workplace with strict rules. After a great deal of hesitation, I finally quit the university in my senior year and returned home. After another great deal of hesitation, I confessed to my mother that I wished to escape from North Korea, since there would no future or hope for me in the country. We wished that our whole family could escape together, but we knew that would be too dangerous, since it would be much easier for authorities to discover our secret plan.

In order to carry out our intention to escape, we decided that I would go ahead first, and that the rest of the family would follow later. I went to Hyesan located in the border area adjacent to China to meet with a broker. The broker would do almost anything for money, including human trafficking. I handed money to the broker and stayed at his house for about two weeks. During the stay, I contacted our relatives living in Japan.

The relatives submitted all necessary documents proving that I am a second generation child of former ethnic Korean residents in Japan. This worked and I was sent to the Japanese consulate in Shenyang, China. I was so excited to hear that they would be protecting me at the Japanese consulate. It turned out, however, to be more difficult than we ever expected.

A total of ten North Korean defectors, including me, were accommodated in a very small area. My room was surrounded by a thin wall, there was one shower and a toilet, and there was space for only a few defectors. It was great that I was safe there, but I found that no one knew when I might reach to Japan. In fact, at that time there was no guarantee that I would ever get to Japan at all.

We could not go out of the consulate because the Chinese authorities were waiting to arrest us and return us to North Korea. There was no way to find out how my family was doing. Of course, we had no cell phones. Actually, we had nothing with us. We had a TV set showing programs broadcast by Japan Broadcasting Corporation, but ironically we didn’t understand the Japanese language. We didn’t know what to do or how to fill our days. We got three meals a day, but the greasy Chinese food didn’t agree with my stomach. Those days were not pleasant, they were painful. But I patiently, single-mindedly waited every day, hoping that tomorrow I might be released to go to Japan, or maybe the day after.

At one time, however, I was almost ready to run away, even if I might be caught by the Chinese authorities and sent back to North Korea. At least I might see my family again, I thought. At one point I felt so desperate I went on a hunger strike. But, none of the employees working at the consulate gave us any information about what was going on outside. They probably thought that if they told us anything we might become upset or frantic.

Since I had no idea when or whether I would be able to reach Japan, various thoughts went through my mind, including the probability that, after all, I could be deported back to North Korea. I began thinking that maybe I should just go ahead and run back to North Korea. Also, there was one window from which I could see the US embassy right next door, and so I sometimes wondered if I should just climb over the wall into the US embassy. Maybe they could make arrangements for me to go to Japan. These ideas haunted me every day for a year. Then finally, after one entire year, the Japanese consulate issued permission for me to move on to Japan.

My flight from there to Japan was my first ever time in an airplane. However, another ordeal awaited me in Japan. I didn’t understand the language. I only knew the Japanese words for apple, good morning, mother and father. My cousin in Japan came to see me at the airport, but he was born and raised in Japan, so that he spoke no Korean. To communicate, we each held a Korean-Japanese dictionary and pointed at words.

I stayed for a while in a rural area of western Japan. While there, I repeatedly tried to reach my family in North Korea, but was not able to connect with them. To this day, I have not yet heard from my family.

While staying in the Japanese consulate, and for some time after arriving in Japan, I had nightmares. Nightmares – there were so many. In one, it seemed that I was captured and sent back to North Korea. In another, I successfully escaped but I somehow ended up killing myself. In yet another nightmare, my parents told me that they were cutting me off forever and adopting a child to replace me. The nightmares continued for another half a year even after I landed in Japan.

After I had been in that rural area for about six months, I started to feel uncomfortable. In the rural area, it was easy for neighbors to notice a newcomer like me, and the neighbors gradually discovered who I was. So, my relatives told me not to go out. This was mentally and emotionally tough on me.

Fortunately, however, I had a chance to talk over the phone with a former North Korean defector, who had settled in Japan. Through this person, I got to know the NGO named Life Funds for North Korean Refugees (LFNKR).

I heard that there was to be a party in Tokyo to celebrate the human rights award granted to LFNKR by the Tokyo Bar Association, and I decided to go to Tokyo for the first time to join the party. During my stay in Tokyo, I discovered that there is a junior high school in Tokyo that provides night classes.

Using the cell phone I borrowed from my cousin, I called a teacher at the junior high school. Back then, I barely spoke Japanese – I probably knew less than 50 words. By connecting all the Japanese words I knew, I managed to communicate my enthusiasm for studying at the night classes. The teacher told me the date that I should visit the school.

My cousin agreed with my decision to move to Tokyo for the night classes. The teachers at the school were very kind and were enthusiastic in helping students learn. I studied the Japanese language, and when I reached a certain proficiency level, I was able to graduate. That took about one year. Then, upon recommendation, I was admitted to a high school run by the Tokyo metropolitan government. While a freshman at the high school, I became very self conscious about my age, so I decided to take an exam that would let me graduate in two years instead of three. I passed the exam and received my high school diploma.

After that, I decided to go to a college where I received training to become a medical worker. I graduated from the college and now here I am, working as a medical worker in Japan. And even more, I have become a Japanese citizen.

What I have always kept in mind is to be proud of myself when I see my family again. Recently, I married a Japanese man. My husband is a good man, one that I will feel proud to introduce to my parents when we are together again.

Q&A Session

Q: Do you feel that it was good for you to have escaped from North Korea?

A: Yes, I think it was good, except that my family had to remain behind. In that light, I sometimes wonder if the escape was really good for me.

Q: Have you got any information about how your family members are doing?

A: Well, I know a person from my hometown who reached Japan five years after I did. According to her, there was a rumor that my family members were sent to a prison. But she has not actually witnessed anything firsthand, and I have not seen it with my own eyes, so I cannot believe it.

Q: How do you feel about “freedom”?

A: Like I said, in North Korea, everything is already decided for you from the moment you are born. We are always told the places to go and how we should go, and failing to obey means that your safety is not guaranteed. I was born and raised in such an environment, so I had difficulties when I came to Japan.

For example, when my cousin took me to Uniqlo and said I could pick out any clothes I liked, it felt great choosing my own clothes, but I was at a total loss. So, I picked up the white T-shirt and pair of jeans that lay closest to me. My cousin was surprised and said “Wow, you sure make quick decisions!” It was just because I had no idea what to do with the freedom to choose by myself.

I felt just like a pet animal which, ever since it was a baby, has been trained never to go out of a door and cannot pass that threshold, even if one day she is told it’s OK to go outside.

Q: Can’t you choose whom to marry by yourself?

A: No, basically not. Arranged marriages are standard for the offspring of ruling elite families, security staff and so on. According to rumor, when men are released from military service, they are not allowed to marry non-military women to prevent the leakage of military secrets. They are forced to marry women having similar backgrounds.

I have heard that the released soldiers must choose, at random, from photos of bride candidates, but that the pictures are placed face down, and they are required to marry the woman in the photo they select. Once married, they live in the same apartment houses to keep the military secrets safe.

Persons like my family, who moved to North Korea from Japan, marry others who have come from Japan. This is a social convention because, if they marry a native North Korean, that person’s career is likely to be badly affected. This is the same with members of the Workers Party of Korea.

Q: What is the “Paradise on Earth” campaign?

(Note by LFNKR: Becoming convinced by a prolonged propaganda campaign that described North Korea as a paradise on earth, over 93,000 ethnic Korean residents in Japan, including at least 7,000 native Japanese wives and children, immigrated to North Korea. The Japanese wives were told that they would be free to come back to Japan in three years if they wanted to, but they were never allowed to.)

A: I think my parents got on board the ship bound for North Korea filled with hope and believing in the propaganda. They were told that education and everything would be free. From my experience, I thought it was impossible and couldn’t be true, but back then my parents believed otherwise and were sure it was all possible.

As their ship approached landfall in North Korea, the passengers expected to see crowds of people waving their arms and holding bundles of flowers. As their ship got closer to shore, however, they could see that the people waving their arms were dressed in tattered white blouses and black skirts. The moment they realized the truth, they knew they had made a huge mistake and cried.

The place where each person was supposed to go after arrival had already been decided. They were led to various train platforms. When my parents arrived at their specified train station, they were awaited by many people who had previously moved from Japan. The people were asking eagerly, “Why did you come? Do you have any Japanese magazines or books? If you have, please can I have one?” My parents called the scene unforgettable.

Apparently, it was true that education was free in the 1970’s and 1980’s. During that time, people, including school teachers, lived on government-supplied rations. In my parents’ time, people could go university for free if they studied hard. Beginning in the 1990’s, however, terrible starvation became widespread. Several million died of hunger as rations halted completely. Nobody, not even the school teachers, received their rations. This meant that if we wanted to go to university, bribes were necessary, and it had to be in dollars or yen, not in our own currency. At that time, if we heard that someone was going to university, it meant that his or her family was extremely rich.

Q: What was the Arduous March (from late 1990’s to early 2000’s) like?

A: At that time we couldn’t even find small fish to eat because we had fished out every swimming thing in the rivers. We could not go fishing out at sea, because it was too far; there was no gasoline or other fuel to get there. The hills all around us were completely denuded because people had cut down every tree, every bush to heat their homes. We continued to dig up coal for cooking and heating, but finally, this also was gone.

Electricity? We received electricity for barely one hour in 24. And if we happened to get electricity for that one hour, the voltage barely reached 80 volts, even though standard voltage in North Korea is 220 volts. Everybody jumped on to grab the electricity at the same time, so the power was overloaded, and all we could get was barely enough to light one filament of a bulb. Everybody was desperately trying to get electricity by slapping and hammering their transformers in frustration. It is as bad as no electricity.

In Pyongyang, there are quite a few high-rise apartments. When I was a university student, one of my friends lived in a 30-storey apartment building. Her apartment was on the 28th floor, but the elevator was never available because of the lack of electricity. So, one morning, she left home for the university and then suddenly realized, halfway down the stairs, that she had left something at home.

She had no choice but to continue on down the stairs; otherwise, she would be late for a morning class. Buses were always overcrowded with commuters. Trolley buses were discontinued because of the lack of electricity, so there would be only one gasoline powered bus per hour or so. Throngs of people would be waiting at a bus stop to try desperately to get on when it came. Often, the men, being physically stronger, grabbed all available space on the bus while many women missed their ride. They simply had to walk because they could not afford to wait another hour for the next bus. Walking for an hour or two is commonplace, even in Pyongyang. The lives of people living in rural areas are even more difficult.

Also, during the Arduous March, when we didn’t have food, the government directed us to eat the roots of corn plants. People usually believe what their government tells them, right? So, we did, we ate corn roots. And most people suffered from serious diarrhea. In fact, many actually died from the terrible diarrhea. Later, the government found that eating corn roots would be harmful, so next they told us not to. Back then, even all the grass on the hills and mountains was already gone. We could find no grass left to eat.

In late 1990’s, many people died in North Korea. In particular, intellectuals such as scientists and educators, who were very serious-minded, died first. Any intellectuals who survived were those who used their expertise as their tools. For example, doctors started to sell medicines, or engineers made things to exchange for food. Other people who had worked in factories began making things at home to sell. The government could no longer control them and had to ease their control because they finally realized that the people would all die under their control.

Thus, only those people who had some kind of tools or skills for self-reliance survived. One widespread rumor back then was that “grass-eating people” all died, leaving only criminals, such as con-artists, murderers and robbers to survive.

This happened back when I was in elementary and junior high school, and I was always afraid. I, understandably, hesitated to go outside much. There actually were murders, and many people died from hunger.

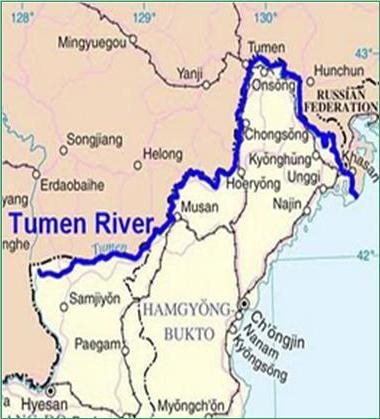

Q: I hear that North Korean border guards shoot North Korean defectors trying to cross the Tumen River.

Almost all North Korean escapees cross the Tumen River

A: To answer your question, let me tell you about when I crossed the river to escape into China. It was the end of October and the river had already started to ice over. River bank areas where the river is wide have fewer border guards, since not many people try to cross there. At river bank areas where the river is narrow, the security is much stricter, and border guards more frequently patrol the river.

So I chose a place where the river is wider. I had heard that many people try to cross the river after dark, and also that the security is less strict in the day, during lunch time. That is why I decided to cross during lunch time.

There were 3 or 4 persons other than me on a hill by the river waiting to seize the right time to dash into the river. I think the river at that place was about 50 meters wide. But, I gave no thought at all to how deep the river was, nor anything else. I just dashed down the hill and onto the road, then I jumped into the river. The river current was faster than I had expected. Oh and, by the way, I cannot swim. I was wearing thick winter clothing, and my clothes quickly got even heavier as they absorbed more and more water.

There are lots of big rocks on the river bed, and those rocks are slippery. The river current is fast. I repeatedly slipped on the rocks. When I reached a point that was almost midway across the river, I heard a loud voice behind me shout “Freeze!” I assumed it was the voice of a border guard, and that any moment I would be shot and die. Whether I go forward or backward, I thought, I could be killed either way, so I decided to keep moving forward.

Fortunately, I managed to reach the other side of the river without being shot. When I turned and looked back across the river, I saw that it had not been a border guard, but a farmer. The farmers living in that area are told to inform the border guards if they see any defectors.

Earlier, someone mentioned medicines. We don’t have pharmacists, and hospitals are not operating, so people with no medical licenses sell medicines they buy in China. During summer vacation, once, I went to visit a friend who was about 20 years old, but she was not at home. I asked her parents where she was, and they said that she died from taking a cold medicine. Can you believe that? She died because she took a medicine supplied by an individual who bought the medicines from China, while he has no medical knowledge or background?

Of course, persons working in hospitals are qualified to provide medicines, but there are scant medicines for the patients. Besides, sick people cannot even see a doctor unless they can offer bribes.