I Was a Political Prisoner at Birth in North Korea

My Family Background

My North Korean name is Shin In-kun (South Korean name: Shin Dong-hyuk). I was born on 19 November 1982. I was a political prisoner at birth in North Korea.

According to what I know from my father, Shin Kyong-sop, he was born in 1946 in the village of Yongjung-ni in Mundok District, South Pyongan Province, near Pyongyang, North Korea. He was the 11th of 12 brothers. It was in 1965, when he was only 19 years old, that great tragedy struck his family.

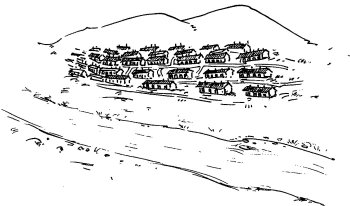

One night, before dawn, policemen rushed into his house, carried away all the furniture, and loaded the entire family onto a truck. It took all day before they arrived at the camp No. 14, operated by the State Security Agency (SSA).

From the moment they arrived there, they were all separated and treated as beasts. With a few rare exceptions of meeting his younger brother in the same prison block, my father knew nothing about his brothers after this. My father was appointed to work in the mechanics’ unit in the camp, and he did his job so well that one day my father was rewarded with the news that he would be allowed to wed a female inmate, Chang Hye-kyong. They became husband and wife from that time on.

From the moment they arrived there, they were all separated and treated as beasts. With a few rare exceptions of meeting his younger brother in the same prison block, my father knew nothing about his brothers after this. My father was appointed to work in the mechanics’ unit in the camp, and he did his job so well that one day my father was rewarded with the news that he would be allowed to wed a female inmate, Chang Hye-kyong. They became husband and wife from that time on.

They were allowed to be together for a mere 5 days or so before they were separated again. From that time forward, my father and mother were not allowed to see each other with the exception of some rare special favor in recognition of some outstanding performance in their work duties.

I know I have a brother who was born a few years before me, but I have little memory of him. I saw him only 3 or 4 times until 1996 when he was executed in the camp. He may have lived with my mother and me when we two brothers were very young. Nonetheless, I have no memory of him in the same house with me nor do I have any memory of him in my early days.

My Early Days

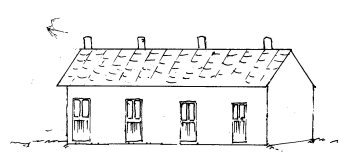

I was able to live with my mother for the first 12 years of my life. My mother was a farmer, starting work at 5 o’clock in the morning and returning home at 11 o’clock in the evening. She was always so busy and I have little memory of any affection between mother and a son.

She brought home 900 grams of corn for herself and 400 grams for me, along with 3 pieces of cabbage, marinated in salt, and a very small bucket full of coal. In fact, she finished work at around 9:30 in the evening but was forced to attend a daily Ideology Struggle Session for one and a half hours.

She brought home 900 grams of corn for herself and 400 grams for me, along with 3 pieces of cabbage, marinated in salt, and a very small bucket full of coal. In fact, she finished work at around 9:30 in the evening but was forced to attend a daily Ideology Struggle Session for one and a half hours.

In reality, the objective of these sessions is to punish prisoners for failure to accomplish a work quota, violation of rules, etc. During this time, prisoners are forced to accuse each other and beat fellow prisoners. From 11 o’clock, it is curfew and no prisoners are allowed to be outside their shelter. This is a standard routine for all prisoners in the camp.

I faintly remember that I often toddled my way to her work with her but she was always so busy that she did not have any time to show me her love. Today, I remember my mother but have no special feelings for her.

I remember that one day I was sent to the 5-year course primary school in the camp where we learned how to read, write, add and subtract, and nothing else. I have no memory of the first day of school. I now remember that there were some 30 children in each class, two or three classes each grade up to fifth grade leading to a total number of some 400 children. I was never curious about where they came from – they were either born there like myself or arrived in the camp as children.

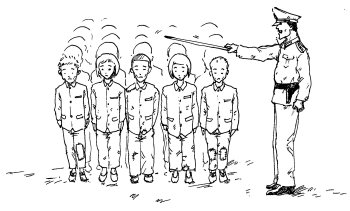

One day when I was 9 years old, my school teacher, always in SSA uniform, searched the children and found 5 grains of wheat in the pocket of a girl. He made her kneel directly in front of us and in full sight, then began to beat her head fiercely with a baton for about an hour until she fainted. It was strange to me that her head never bled but many bumps raised on her scalp from the punishment. We carried her to her house, and were told the next day that she had died quietly the night before.

One day when I was 9 years old, my school teacher, always in SSA uniform, searched the children and found 5 grains of wheat in the pocket of a girl. He made her kneel directly in front of us and in full sight, then began to beat her head fiercely with a baton for about an hour until she fainted. It was strange to me that her head never bled but many bumps raised on her scalp from the punishment. We carried her to her house, and were told the next day that she had died quietly the night before.

A child was beaten to death and no one was held responsible nor punished! The school teachers in their SSA uniforms had the right to do whatever they liked. This is a common and almost routine case in the camp No. 14, not an isolated or exceptional case.

Once, when I was 10 years old, I followed my mother to work in the rice fields, as the children had been ordered to help their mothers plant the rice. The work began at 9 o’clock in the morning and we were under strict order to accomplish the work quota. On that particular day, my mother was quite weak and already somewhat pale in the morning. She complained about a headache. No one was excused from the work as this was the rule in the camp. I worked very hard to help my mother. Nevertheless, our work was very slow.

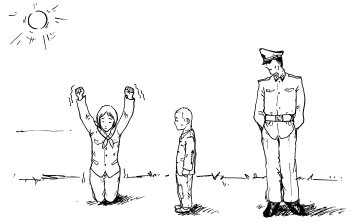

The SSA officer was furious with our slow work. My mother was ordered to sit on her knees on the paddy road with her hands raised straight up in the sun when all other prisoners were having lunch. Helplessly, I looked on. Precisely an hour and a half later, the SSA officer came to her and ordered to start work. She was already weak, badly punished, and had no lunch. Nevertheless, she did her best to do the work until she fainted at around 3 o’clock in the afternoon. That night she sat on her knees for two hours and some 40 prisoners accused her of being lazy at the dreaded punishment session that evening.

When I was 12 years old, I was sent to middle school and then to work from there on out. I was separated from my mother to stay with other children. There was no actual class in the middle school. We were given all kinds of work – weeding, harvesting, carrying dung, etc. No study, all work.

When I was 12 years old, I was sent to middle school and then to work from there on out. I was separated from my mother to stay with other children. There was no actual class in the middle school. We were given all kinds of work – weeding, harvesting, carrying dung, etc. No study, all work.

Power Plant Construction Work

We children were mobilized for the work of installing a medium-sized power plant during the period from spring of 1998 to the fall of 1999. We were between 13-16 years old.

During this period, I saw so many children killed by accidents. I used to see public executions and dead bodies, but this was the first time I witnessed to many children who were killed by accidents. Sometimes, 4 to 5 children were killed a day.

On one occasion, I actually saw eight people killed by an accident. Three plumbers were working high up on a tall cement wall, three 15-year-old girls and two boys were helping them with mortar below. I was carrying mortar to the children when I saw the cement wall falling. I shouted, “Look out! The cement wall is collapsing!” It was too late and 8 people were buried under many tons of mortar. No rescue work took place. The security officers just shouted at us, “Don’t stop your work and keep working!” Once again, this was not an isolated case but only one of many such cases in the camp.

I Was Tortured by Scorching

At around 8 o’clock in the morning, 6 April 1996, I was ordered to report to school immediately. When I arrived at the school, I noted a passenger car waiting at the school. The people who emerged from the car approached me, no questions, hand-cuffed and blindfolded me and drove me to an unknown location. I felt like we were descending in an elevator, and I found myself in a dark chamber illuminated only by a single light bulb, when they removed the scarf from my eyes.

Directly before me was a man sitting at a desk in an empty room. He gave me a sheet of paper and told me to read it. There appeared the names of my father’s brothers, two of whom had collaborated with South Korea during the Korean War and then fled to South Korea. This is the very first time I understood why my father and his brothers were brought here. I wrote my name and placed my fingerprint at the bottom of the document.

This was a secret underground torture chamber in Camp 14. I was in cell No. 7, a dark and small room with no light except a small electric light on the ceiling. There I was told that my mother and brother were arrested at dawn that morning while attempting to escape from the camp, and I was told to tell him all about a family conspiracy.

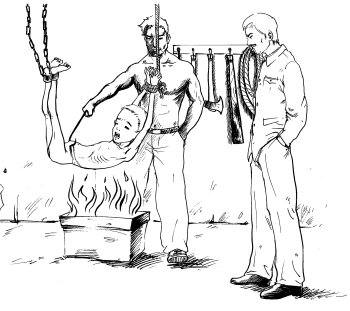

This was an awful and unthinkable crime and I jumped with surprise at the news. The next day I was taken to a chamber, full of all kinds of torture instruments. I was stripped, my legs were cuffed and my hands were tied with rope. I was hung by my legs and hands from the ceiling. Some one told me to confess the truth about who started the escape plan. I said I had known nothing about it.

Strangely, I had no fear at that moment. Even today, my lack of fear at that time remains a mystery. Someone started a charcoal fire and brought it just under my back. I felt the heat at my waist and shrieked. I instinctively struggled hard to avoid the flames. My torturers pierced me with a steel hook near my groin to stop my writhing, then I blacked out.

I don’t know how long I was unconscious but I found myself in a cell that rocked from my own feces and urine. I summoned all my strength to get up but felt great pain at my waist. I found blood and wounds at my lower abdomen. As days passed, the pain grew and my flesh began to decay, stinking so terribly that the guards avoided entering m y cell. Next, they moved me to a cell opposite to mine. A very elderly person was in it. He said he had been imprisoned for well over 20 years. He had been reduced to skin and bones. He did not divulge any more about himself, but I will never forget how he quietly helped me in my time of need.

I don’t know how long I was unconscious but I found myself in a cell that rocked from my own feces and urine. I summoned all my strength to get up but felt great pain at my waist. I found blood and wounds at my lower abdomen. As days passed, the pain grew and my flesh began to decay, stinking so terribly that the guards avoided entering m y cell. Next, they moved me to a cell opposite to mine. A very elderly person was in it. He said he had been imprisoned for well over 20 years. He had been reduced to skin and bones. He did not divulge any more about himself, but I will never forget how he quietly helped me in my time of need.

Once, as he gave me half of his food ration, he said, “you are a young boy and you need this food to stay alive.” With his kind attention and, perhaps by the grace of God, I began to eat and my health began to improve. One day after many months sharing a cell with him, I was finally summoned by authorities and transferred. This was the last time I saw the old man, a living skeleton, who had been so kind to me. I will never forget him and came to love him more than my parents. This was the man who instilled in me a strength of will that my parents had never been able to give me.

I was next brought to a room and found my father on his knees on the floor, and I learned for the first time that he had also been arrested at the same time as I had. We were ordered to be fingerprinted and to sign an affidavit saying that we would keep secret everything we knew about the place and would tell nobody about what happened to us or what we had seen. This was on November 29th 1996.

My Mother and Brother Publicly Executed

Then, we were blindfolded again and taken outside. I had been kept in an underground cell without sunshine about 7 months. They next took us to a kind of public square where a crowd of people had gathered. I recognized the place as a public execution site that was used 2 to 3 times every year. The hand cuffs were removed from our wrists, and we were told to sit in the front row of the crowd. We saw 2 convicts, a man and a woman, being dragged to the site from some distance. As the convicts were dragged closer, to my shock, they were my mother and brother!

My brother was obviously very weak, his bones clearly visible beneath his skin. My

mother seemed swollen from head to foot and her eyes were inflamed. An indictment was read aloud, the details of which I don’t remember, except the final words, Chang Hye-kyong and Shin Ha-kun, enemies of the people, are sentenced to death.’

My mother was first executed by hanging and, then, my brother by a firing squad. I simply could not bring myself to witness their murder. I looked at my father when the moment came. Tears were running down his cheeks and gaze was fixed on the ground.

My mother was first executed by hanging and, then, my brother by a firing squad. I simply could not bring myself to witness their murder. I looked at my father when the moment came. Tears were running down his cheeks and gaze was fixed on the ground.

After the execution, I was again separated from my father: He was sent to work on a construction site, and I was sent back to school. Things were no longer as they used be, I was now deemed the son and brother of traitors. Teachers just punished me repeatedly and arbitrarily for little apparent reason, and I was the target of constant discrimination. I urinated in my trousers many times as my teacher did not allow me to use toilet. I can never remember not being hungry. One day, I discovered 3 kernels of corn in a small pile of cow dung, picked them up and cleaned them with my sleeve before eating. As miserable as it may seem, that was my lucky day.

My Niece Raped

My niece was among a group of prisoners collecting acorns up on a hill one day when they were spotted by guards. My aunt and sister were separated from the group for questioning as to why they were so close to the barbed wire fencing.

My cousin was 21 or 22 years old at that time and was very pretty. Two guards began to fondle her, as her mother bitterly protested. The guards tied her mother up to a tree facing the trunk and blindfolded her. They then proceeded to rape her daughter in broad day light.

My aunt fainted. When she woke up, she found her daughter naked and lying unconscious on the ground and having trouble breathing. The guards were nowhere in sight, My niece never recovered consciousness.

Her mother wailed in a loud voice and told everyone she met in the camp about what had happened. Soon afterwards she disappeared, and no one knows what happened to her. This is how members of our family disappeared one by one.

Perhaps, my father’s family line will disappear entirely from the earth. As tragic as it is, this is not only my family’s story. The fate of all 40,000 to 60,000 prisoners in the camp

At the Garment Factory

I finished middle school and was assigned to work as a sewing machine repairman at a garment factory. There were a total of about 2,500 prisoners in the garment factory; 2,000 of them were women. There were a large number of young women in their 20s, 30s and 40s, and many of them were quite attractive.

The women were not provided with proper uniforms, so their breasts were easily exposed to the prying eyes of SSA officers. Seven good looking women are selected to do the cleaning of SSA camp offices. Not surprisingly,. many women vie for this position because they are able to escape the normal kickings and beatings while at work. Even the risk of occasional sexual abuse is considered profitable for the usual violence and wrath of SSA officers.

Park Yong-chun was a pretty girl from the same class as me and would be 25 years old now if she were still alive. She was picked to do the cleaning job in the camp office. One day, we discovered that she was pregnant. There were 4 of us from the same class, and we did our best to cover up her pregnancy. She would certainly disappear if found to be pregnant. But her pregnancy was soon discovered and she did disappear completely. No one knows what happened to her. This is what can happen to any women prisoners who clean the offices of camp officers.

One day, I was carrying a sewing machine base up to the 2nd floor when it dropped, as my arms became fatigued. As punishment, my middle finger was cut off

Sometime in mid-2004, late in the evening, just as the daily punishment session was over, when 4 SSA officers strangely appeared and asked us “Which cell has the largest army of lice?” Some prisoners responded, “Yes, we have a lot of lice.” The SSA officers said, “Ok, then, use this water to clean your body.” And they gave a bucket of water to a group of seven women in a cell and the other bucket was given to a group of 5 men in another cell.

Sometime in mid-2004, late in the evening, just as the daily punishment session was over, when 4 SSA officers strangely appeared and asked us “Which cell has the largest army of lice?” Some prisoners responded, “Yes, we have a lot of lice.” The SSA officers said, “Ok, then, use this water to clean your body.” And they gave a bucket of water to a group of seven women in a cell and the other bucket was given to a group of 5 men in another cell.

Nothing immediately happened when they washed their bodies with the water, except that the water looked somewhat milky and had the same odor as the insecticides used in the fields. However, in about a week, red spots appeared all over their bodies, which began to fester. Within a month, their bodies were covered with running sores.

They simply could not get up for work. When we thought that they were about to die, a truck came one day and carried them away to an unknown location. Had I washed my body with that water at that time, I would surely not be here today.

One day in 2004, a Park (I am unable to remember his given name), a young North Korean prisoner, was assigned to my section of the garment factory. I was instructed to show him how to operate machines. We became good friends and through our conversation he opened up my eyes to the outside world for the first time. This young man had the experience of traveling in several countries in Asia and told me so many things about his experiences in the outside world. He encouraged me to escape from the camp at the first opportunity and to experience for myself a world outside my existence in the prison camp.

Escape from the Camp

On 2, January, 2005, about 25 of us, men and women including Park, went up to the mountain to collect firewood. I was in the lead. I suddenly found barbed wire in front of us. I looked at the other prisoners around me who were all busy collecting fire wood.

At this moment, a memory flashed through my mind: of my mother and brother being executed, and the nightmare of the torture I experienced afterwards. Carefully, Park and I approached the barbed wire. I had no fear of being shot at or electrified; I knew I had to get out and nothing else mattered at that moment..

I ran to the barbed wire. Suddenly, I felt a great pain as though someone was stabbing the sole of my foot when I was passed through the wire. I almost fainted but, by instinct, I pushed myself forward through the fence. I looked around to find the barbed wire behind me but Park was motionless hanging over the wire fence!

At that desperate moment I could afford little thought of my poor friend and I was just overwhelmed by joy. The feeling of ecstasy to be out of the camp was beyond description. I ran down the mountain quite a way when I felt something wet on my legs. I was in fact bleeding from the wound inflicted by the barbed wire. I had no time to stop but sometime later found a locked house in the mountain.

I broke into the house and found some food that I ate, Then I left with a small supply of rice I found in the house. I sold the rice at the first mining village I found and bribed the border guards to let me through the North Korean border with China with the money from that rice.

My Way to Freedom

As I was born a political prisoner, it was only when I had escaped that I saw North Korean society for the first time. I only saw it for 20 days, as I was miraculously able to cross the frozen Tumen River and safely arrive in China in January, 2005..

For about one year, I worked at a Chinese logging site at a remote mountain near the border and was given an amount of Chinese Yuen, equivalent to about 90 USD, for that entire year’s work. I arrived in Quingdao via Changchun and Beijing by train and bus.

I begged a South Korean man at a Korean restaurant in Quindao for help. He took me to Shanghai and managed to bring me into the South Korean Consular office there. I am here in South Korea after spending 6 months in the Korean Consular Office in Shanghai.